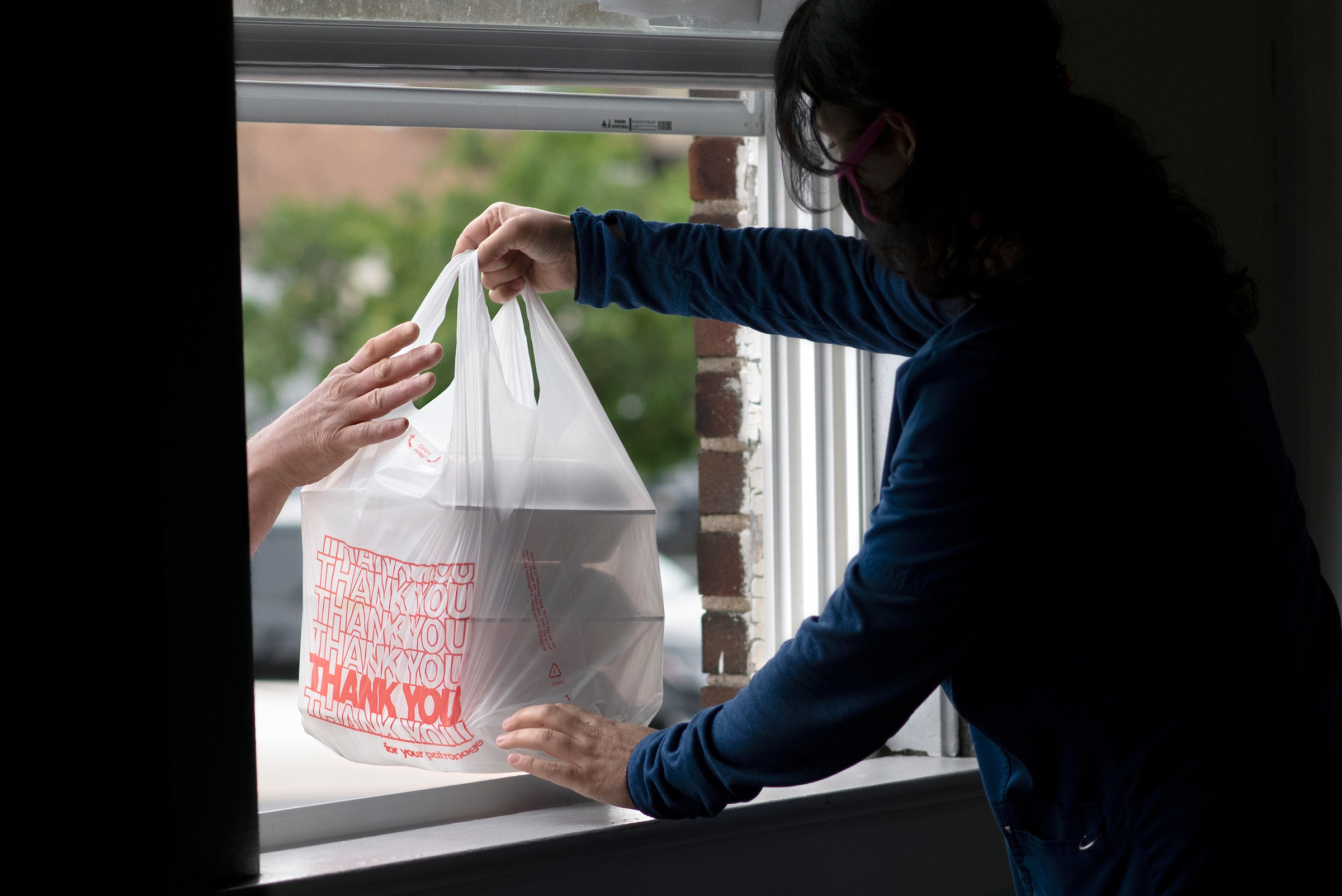

It’s a little after 4 p.m. on a Thursday, and another of Talia Rodriguez’s neighbors has walked up to the open window of a church on Buffalo’s west side. The sign on the window reads, “Pick up meals here.”

Yes, free food is distributed two afternoons a week here at Asamblea de Iglesias Cristianas (Assembly of Christian Churches), but that window opens to far more — a deep sense of community, commitment, and solidarity in a diverse, multilingual area of this city in western New York.

The church has been distributing free food for more than three years. Volunteers know most of the clients who come to the window, and conversations and shared laughter are common.

“We’re all neighbors helping neighbors,” said Rodriguez, associate director of West Side Promise Neighborhood (WSPN), a network of 35 organizations working to improve the lives of residents in the areas west and north of downtown Buffalo.

Volunteer Wanda Torres hands a hot meal to a neighbor at Asamblea De Iglesias Cristianas. The meal distribution, which is offered on Tuesdays and Thursdays, is a part of the West Side Promise Neighborhood effort to improve the lives of residents.

Members of the network include colleges, businesses, medical and financial institutions, arts groups, community centers, and others. Together, they’re working to support neighbors from “cradle to career.” Much of that energy, especially since the pandemic began more than a year ago, is devoted to ensuring people in the community have food, utilities, and other basics.

Inside the Asamblea de Iglesias Cristianas dining room, volunteers assemble dozens of hot meals packaged with fruit, salad, yogurt, juice, and dessert. The church is one of dozens of pantries and food security sites in a city where 30 percent of its 255,000 residents live in poverty, according to the U.S. Census.

Buffalo’s west side is largely made up of tightly packed homes, small businesses and industries, ethnic churches, and dollar stores. A few miles away in other neighborhoods, the vibe is more affluent, with trendy restaurants, cafes, brew pubs, and food co-ops.

A 2019 community snapshot led by the University at Buffalo Regional Institute found that 54,000 residents west of Buffalo’s Main Street live at or near the poverty line. Add a language barrier — and the closing of a full-service neighborhood grocery store in 2019 — and the struggle for food security has become more difficult.

Talia Rodriguez, center, associate director of West Side Promise Neighborhood, prays with volunteers before distributing food at Asamblea de Iglesias Cristianas. Many of the volunteers have experienced food insecurity themselves, Rodriguez said.

West Side Promise Neighborhood’s members are working hard to close a gap that has been a reality for generations, collaborating with established organizations like Feed More WNY and Hearts for the Homeless.

“(Many of) the volunteers here have experienced food insecurity,” Rodriguez said of Asamblea de Iglesias Cristianas. That includes Rodriguez herself.

As a child, she and her family attended Asamblea de Iglesia Cristianas, which also serves meals after Sunday service. She now brings her four-year-old son to the church.

“I didn’t realize that a part of the reason we came to church was so we could get food,” Rodriguez said of her childhood. “This is a place of fellowship and no judgment. You can (receive) food and not have shame. That’s what we’re working toward.”

Talia Rodriguez, a fifth-generation Buffalonian, runs West Side Promise Neighborhood from the Office of Civic Community Engagement at SUNY Buffalo, a community partner. As a child, she and her family attended Asamblea De Iglesia Cristianas, which has served free hot meals for more than three years.

Church congregations on the west side reflect the diversity of languages spoken in Buffalo. A church several blocks from Asamblea de Iglesia Cristianas advertises two Sunday afternoon services — in Burmese at 1:30 p.m., and in Spanish at 4:30 p.m.

According to 2019 U.S. Census data, almost one-fifth of the city’s quarter-million residents speak a language other than English at home; more than 10 percent were born in another country.

Thousands of refugees have settled here in recent decades, joining generations of immigrants and others who helped the city grow after the completion of the Erie Canal almost 200 years ago.

The estimated number of languages spoken in Buffalo ranges from 40 to 80 — English, Spanish, Polish, Italian, and Arabic are the most common, followed by dozens of others.

That’s where resources like findhelp.org can make a difference. The website hosts a nationwide platform that connects people to social services in their area. Findhelp’s translation feature enables multilingual communities to access services in their preferred language.

In Buffalo, Rodriguez uses a localized version of findhelp.org called The Community Resource Link, hosted by BlueCross BlueShield of Western New York. With the site’s translation features and texting capabilities, Rodriguez can text other local programs to her clients at the food pantry if they need something else.

“This is why I sought out [The Community Resource Link and findhelp.org],” Rodriguez said. “Some neighbors need clothes. Now we can ask. We’ll have the immediate ability to increase access to services. [Findhelp] bridges the technology divide.”

Rodriguez, 31, is a fifth-generation Buffalonian who speaks English and Spanish, and whose lineage includes Sicily, Ireland, and Puerto Rico. She’s a whirlwind of energy and passion, talking quickly and efficiently, and almost always in motion.

She runs WSPN from the Office of Civic and Community Engagement at SUNY Buffalo State College. She earned a law degree from the University at Buffalo and is studying for the New York State bar exam while working, volunteering, and caring for her son.

In addition to making sure neighbors have access to food, she writes grants, sets up summer programs, coordinates efforts with WSPN members, like the local Burmese community, and lends a hand in her church’s kitchen.

“Food security systems will always ebb and flow, but hunger is constant,” Rodriguez said. “People need food co-located in their backyard,” not a long walk away during Buffalo’s bitter winter weather.

Luz Vega, a retired nurse, has cooked and served meals at Asamblea de Iglesia Cristianas with her husband José since the food distribution began. She keeps detailed logs in spiral-bound notebooks listing the number of meals given out through the window each Tuesday and Thursday. (Before the pandemic, guests could eat in the dining room.) On the first day the pantry opened in November 2017, volunteers served 46 meals; on a recent Tuesday, they served 101.

“I do this because it comes from the heart,” Luz Vega said. “You care for the person who has nothing. You want to give them whatever they need, so their needs are taken care of. It feels good, no matter who they are.”

One of the regulars who comes to the window is a Marine Corps veteran who relies on food from the church twice a week, as well as another monthly pantry a few blocks away.

“It helps me out,” said the man, who didn’t want to be identified. “I’m on Social Security, and I have a service dog and cats, so I have bills.”

Volunteers Lizbeth Almodovar, middle, and Luz Vega, right, joke while preparing food at Asamblea de Iglesias Cristianas. “I do this because it comes from the heart,” Vega said.

Another of WSPN’s member organizations, Hearts for the Homeless, operates a monthly mobile food pantry on the west side.

On a recent Friday afternoon in a parking lot behind an apartment building, a steady stream of people arrived on foot and in vehicles to collect vegetables, fruit, yogurt, peanut butter, and bread. Seventy people were served in about an hour.

Faustina Palmatier, a leader in the local Burmese community, arrived at the mobile pantry with five other women from the Karen (pronounced “kuh-REN”) Society of Buffalo.

The Karen are among the many ethnic groups from Myanmar, also known as Burma, in southeast Asia. The local society formed several years ago to support the several thousand Burmese in Buffalo.

Palmatier has been an invaluable resource for the community, Rodriguez said, facilitating access to food and providing translation for social services and other needs.

“We partner with Talia [Rodriguez] and she connects us with the food pantry,” Palmatier said. “Our community is grateful for that.”

Rev. Osvaldo Torres and his wife, Abigail Torres, have been ministering at Iglesia el Calvary Asambleas de Dios in the Black Rock neighborhood on Buffalo’s west side for four years. The Torreses opened a Saturday food pantry in November, during the pandemic.

A mile away in a pre-Civil War building, Rev. Osvaldo Torres and his wife, Abigail Torres, have been ministering at Iglesia el Calvario Asambleas de Dios (Calvary Assembly of God Church) for four years.

Dating back to 1855, the church’s sanctuary is strikingly beautiful, with an intricate web of wooden beams and stained glass windows.

The Torreses opened a Saturday food pantry in November of last year in response to increasing needs in the community during the pandemic. Most of his congregation of about 50 families speak Spanish, but many speak Arabic, Burmese, or another language. Most have large families.

“This is a high-need community,” the Rev. Torres said. “The church is here to help. (Opening the pantry) was definitely a conscious decision. We are a church that takes care of the people here.”

Rev. Torres obtained a grant that will allow him to install freezers and food shelves inside his former office. They want to transition to a “choice pantry model,” which allows neighbors to browse the shelves and select what they prefer.

“It can feel more like shopping,” Rodriguez said.

The church has no parking spaces, but many neighbors don’t have cars anyway.

“They bring shopping carts, and kids bring wagons, whatever they can use to carry groceries home,” Rodriguez said. There is nothing quite like seeing “tears in the eyes of the mothers” when they receive food for their children, she added.

A worker cleans the entryway to a closed down Save A Lot grocery store on the west side. It closed in 2019 after more than 20 years serving the neighborhood.

This summer, WSPN is working to ensure families have enough food for their children while schools are closed.

Through a nine-week program for children at Shaffer Village, a public housing community of 250 units, breakfast and lunch will be served daily for children who live there.

Annika Smith, 19, an Americorps summer associate, will run the program with more than 30 volunteers. They’ll serve food, distribute books, and host outdoor activities in a nearby green space.

“This has never happened here on this scale,” Rodriguez said. “There’s no food in our zip code on Wednesdays.”

She would know. Rodriguez lived here in her mid-20s after spending her childhood in other west side neighborhoods.

Shaffer Village opened in the 1950s, primarily housing white residents, but the community now houses primarily residents of color.

Gentrification is a reality in Buffalo, as in other cities restoring an urban vitality that often comes at the expense of long-time, low- and middle-income residents.

“Rents went up in our old neighborhoods, and we got pushed up here,” Rodriguez said.

Volunteer Andres Almodovar sorts dozens of assembled hot meals, packaged with fruit salad, yogurt, juice and dessert at Asamblea de Iglesias Cristianas as part of the West Side Promise Neighborhood effort to improve the lives of residents.

A few blocks from the Asamblea de Iglesias Cristianas window sits the shell of a Save A Lot grocery store. It closed in November 2019 after more than 20 years serving the neighborhood.

But there are signs of life, signs of hope. Workers recently began cleaning the entryway and parking lot, and there’s talk of a multi-ethnic food store opening there. A new grocery that offers a taste of home for neighbors would also liven up a tired corner of busy Ontario Street and provide jobs.

Soon, perhaps, Rodriguez won’t have to drive past a boarded-up grocery store each time she heads to a food pantry to help feed the community.

As much as a new source of food — and jobs — will help the Riverside and Black Rock neighborhoods of the west side, there’s still more work to be done.

“There are 15,000 people in Riverside alone living in poverty,” Rodriguez said. “We need to insert people of color and people who have the lived experience of food insecurity at the very top of the decision-making tier as it relates to food-systems planning.

“There’s no end date on this,” she said. “We’ll just keep going.”