The last names of students and parents have been withheld at their request.

After struggling with depression and anxiety through two years of high school, Reece discovered marijuana. “My first time smoking, I didn’t have to feel those emotions anymore. I could just push all of that out,” he said.

The summer after his sophomore year, Reece began smoking nightly, then as often as he could. “I figured if I’m already doing it every night, why not do it all day, every day?”

But the more he used, the more withdrawn he became. He stayed home when his family went out for their traditional Saturday lunches. He spent more time alone in his room.

“He was always a fun brother,” said Reece’s mom, Kristine. “Then all of a sudden, he was gone. [His little brothers] didn’t know why, but it was a drastic change in behavior. That’s when we started figuring out what was going on.”

Naming the problem was only half the battle, and the situation got worse before it got better. Reece’s parents caught him taking money from his younger brothers’ piggy bank. He continued to use even as his parents begged him not to. When they gave him one final opportunity to stop on his own, Reece couldn’t do it.

“The option of not using never crossed my mind,” Reece said. “There was always this feeling like I had to use.”

Reece spent less than a week in rehab, then ran away. “Although I was constantly surrounded by really understanding people, I still felt trapped and really alone,” he said. He hid on “some guy’s back porch” for several hours, wrote in his journal, then called his mom to pick him up. Summer was nearly over, and school was starting soon. Kristine wasn’t sure what to do.

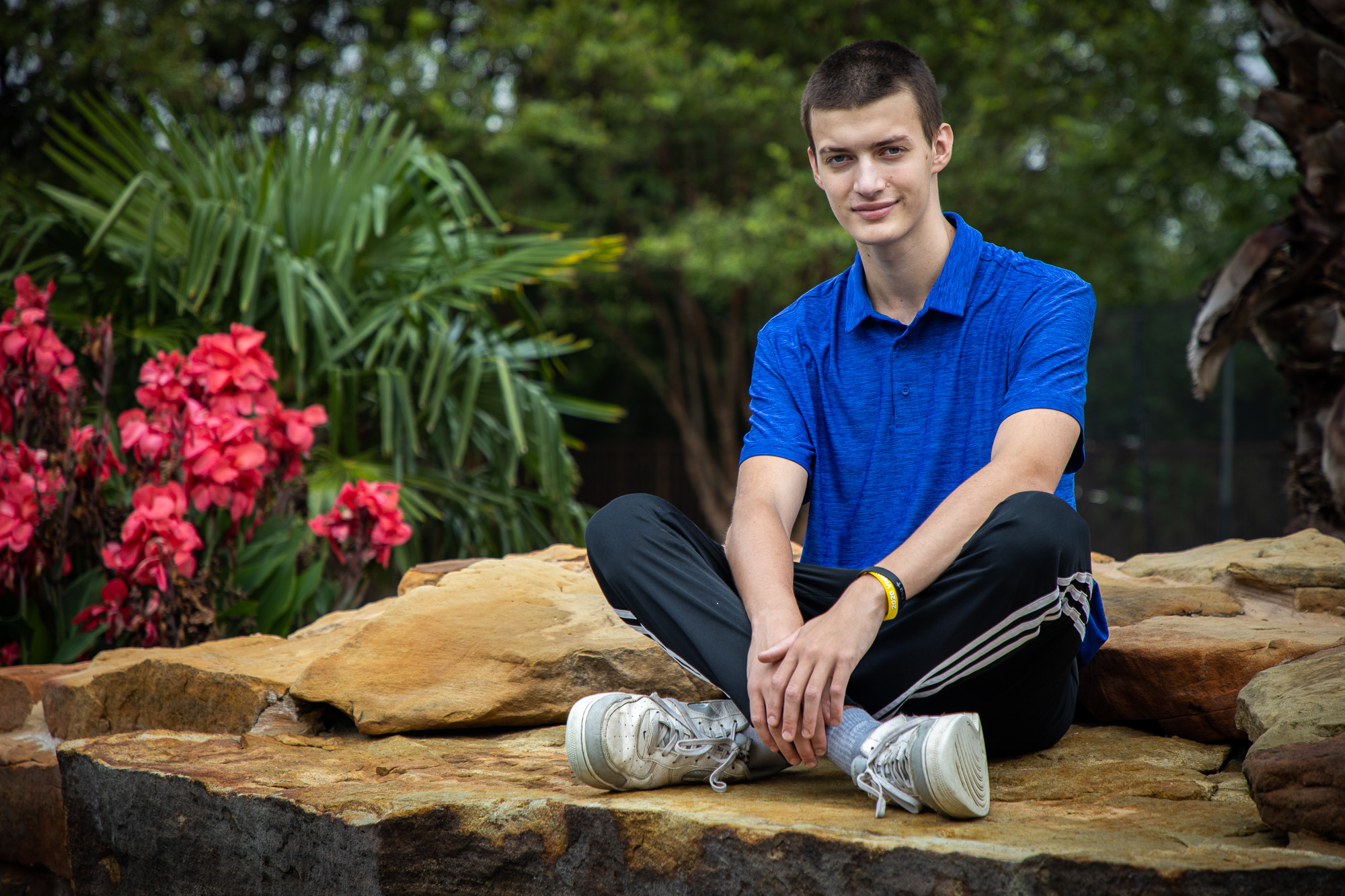

University High School graduate Reece, with his mom, dad, and four brothers at their home in Round Rock, Texas. Reece’s mom Kristine says the culture at UHS provided needed support for Reece. “I could see he was in an environment where people were accepting him and loving him for who he was,” Kristine says. [Photo by Jim Tuttle]

“Going back to the old high school felt like one of the worst ideas, and going to another public high school felt like musical chairs,” Kristine said.

While searching for options, she found University High School (UHS), an academic program for teens recovering from alcohol and substance abuse. The campus was 40 minutes away from their home in Round Rock, but Reece and his parents went to visit.

“It just felt so inviting and caring,” Kristine said, “like these people really get the teens. I found out it’s because they’ve actually been through recovery themselves, and I think the teens feel differently knowing [the staff have] lived it and chosen to help others.”

“Going in and just seeing everyone with really bright faces,” Reece said,” they just seemed to be doing way better than I was, and that was something I wanted to achieve.”

UHS is the only school in Austin, Texas, with a focus on sobriety, and the only school with staff who understand addiction clinically and personally, which offered Reece something public school could not.

“It was really difficult for me to open up about mental health to other people. Because in high school, it’s just not talked about. It’s looked down upon,” Reece said. “But at UHS, they’re willing to sit down with you and listen and try to get a better feel of what you’re struggling with.”

Along with academic programs and credit recovery provided by UT Charter Schools, UHS, which is now part of Austin Recovery Network, builds 12-step recovery support into the school day. Students also join an “alternative peer group,” usually Keystone APG, which is also part of Austin Recovery Network and provides 12-step recovery and peer support for teens and parents outside of school.

Austin Recovery Network CEO Julie McElrath, whose family understands firsthand the disease of addiction, said the wrap-around support for students and parents helps everyone affected by a teen’s addiction navigate recovery together.

“We do a lot of repair work,” McElrath said. “There’s been a lot of trust that’s been broken. Parents are tapped out, they’re not able to hold the space, they lose their temper, [and] kids are pushing them and not being honest.”

Many UHS parents end up joining Al-Anon groups, which provide 12-step support for people who’ve been affected by the addiction of someone they love. This can help parents understand how addiction works, while connecting them with others who’ve lived through the experience.

University High School junior Ella and her mom, Kim, at their home. Ella says she was nervous at first about attending UHS and leaving her former school behind. “When I came here, I was like, whoa! There’s a whole bunch of different kids who are really cool, who I could have met anywhere. But they’re also sober,” Ella says. [Photo by Jim Tuttle]

But relationship repairs run in both directions. “When you’re in active addiction, you don’t realize you’re damaging all the relationships in your life,” said Ella, a junior at UHS. “It’s not just affecting you, it’s affecting everyone you’re around.”

Ella’s mom, Kim, is also in recovery, which Ella says only strengthens their relationship. “It’s kind of cool having a parent who went through the same thing you did,” she said. But Ella was skeptical at first about switching schools, worried she’d miss out on a “normal high-school experience.”

“My mindset before coming here was that everyone drinks sometimes, everyone smokes sometimes. Like, it’s just normal teenage behavior,” says Ella. “You can convince yourself everyone’s doing it, but it’s not true.”

A 2019 report from the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration found that 12.5 percent of teens used marijuana in 2018, while just 2 percent had marijuana-use disorder. By comparison, 9 percent of teens used alcohol, while 5 percent were binge drinkers, and .5 percent were heavy drinkers.

At the same time, only .6 percent of teens received support in the form of in-patient treatment, counseling, or support groups in that same year — far less than the number who struggle with a substance-abuse disorder. The same report says many people don’t believe they need treatment or aren’t ready to quit. Those who are may not have health insurance or funds to pay for costly treatment options.

Unique, therapeutic education options for teens are also rare. The Association of Recovery Schools lists only 45 campuses across the US, and many serve just a small group of students. UHS currently has 17 students enrolled, but has never turned a student away for lack of space or funding.

With the fall semester now underway, UHS is offering all of its classes and support online, a switch they made in March, when the pandemic forced schools to close. Instead of taking off for Spring Break, UHS staff worked to reconstruct the normal schedule online.

“We knew we could not have interrupted services for people who desperately need connection to maintain well-being and recovery,” said UHS Director of Youth Services Irek Banaczyk, who celebrated 13 years of sobriety in January. “Relationship is the heart of recovery, more so for adolescents. And we know that consistent, regular schedules are important for mental health and stability.”

As it always did, the school day begins with a 45-minute check-in — now on Zoom — where students can share challenges they’re facing in recovery, or anything else. Academic work continues until lunchtime, followed by an hour of recovery work. Afternoon activities vary, from social-emotional wellness activities to self-care and service work.

For Reece, the sense of community and openness among students and staff seemed to make all the difference. After his first semester at UHS, he chose an academic plan that allowed him to graduate a year early. The pandemic, in one sense, helped him dig into school work and complete his credits on time. But he also lost the daily interactions he found so valuable at school.

Reece celebrates with his family at the University High School class of 2020 graduation parade in Austin, Texas, in May. Reece was able to graduate a year ahead of schedule at UHS, and was asked to give the senior speech. He recently moved into a sober living home near the University of Texas campus, and is taking classes at Austin Community College. [Photo by Jim Tuttle]

Even so, he was chosen by UHS staff and teachers to give the senior graduation speech, where he told his classmates, “A year ago today, I had no aspirations for my future, other than finding happiness through drugs. But I broke the mold and did what I thought was impossible, and created my own path. Despite other people’s countless doubts, I flew anyway.”

Kristine said Reece started spending time with the family again. “He’ll chase after his brothers sometimes and throw them on the sofa. They love it. They adore being around him. He’s just plain hilarious.”

A couple weeks ago, Reece moved into Alpha 180, a sober living house for college-age men near the University of Texas, just a mile or so away from UHS. He’s attending Austin Community College, studying digital arts, and planning to enroll in a four-year college.

“Now I’m able to enjoy life without having to dread waking up every morning,’” Reece said. “Now I’m motivated and excited to go into a new day and learn how to make peace with myself. I feel a lot more whole as a person.”

The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration provides 24-hour confidential support for people and families struggling with addiction.